Some surprising results in a survey made us think, and findings in recent research suggest a somewhat alarming pattern. It seems we systematically design buildings to suit men, and women are consistently suffering for it. It’s clearly not fair, and we believe it’s time to act upon it.

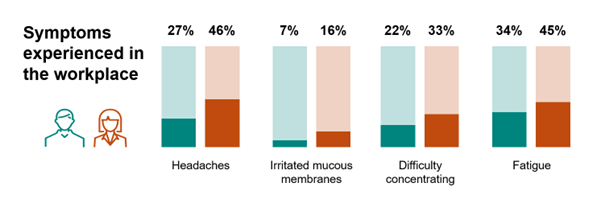

Right before the pandemic, we conducted a substantial survey of over 2000 respondents regarding their well-being at work, and the differences in how men and women responded really made us think. There was a clear imbalance in how frequently we experience a number of symptoms – from headaches and tiredness, to irritated mucous membranes. And while all symptoms are experienced by both men and women, women seemed to be suffering much worse. (Study conducted in Sweden by PFM Research in 2019 on 2003 respondents above the age of 18).

(Study conducted in Sweden by PFM Research in 2019 on 2003 respondents above the age of 18).

Systematic design bias

From this insight we started to look for possible causes, and when going through research on this topic, we realised that the differences could, at least in part, actually be caused by systematic biases in the way we design buildings, especially regarding thermal comfort.

When we design buildings, we do so based on calculations, which are in turn based on assumptions of the standard inhabitant of the building. And this standard inhabitant, often decided on decades ago, is distinctly male. Looking at the average woman and the average man, we are of course very similar, but there are also clear differences in a number of physiological and cultural parameters. And to put it bluntly – if we systematically design buildings to fit male inhabitants, women will suffer the consequences.

Time to look at indoor climate from a gender perspective

In recent years we have seen reports of similar problems in a number of industries, from how we conduct medical trials to how we design the safety mechanisms of a car. But the way we design our indoor environments has largely been ignored from this perspective. Seeing the results, we believe this is an issue worth serious discussion within the industry and research community. How can we take gender into consideration when designing our indoor climate systems? Is it finally time to update the standards?

This could be the next major step in the evolution of indoor climate, but to achieve change, we need to build knowledge on this topic within the industry. We have therefore compiled a summary of relevant research for this particular topic, something to set off the debate. Feel free to download and form your own opinion on what needs to be done next.

.jpg?width=75&name=Image%20(5).jpg)

.jpg?width=75&name=magnus%20andersson_550x550%20(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=75&name=0%20(1).jpg)

-4.png?width=75&name=MicrosoftTeams-image%20(3)-4.png)